Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a specific developmental disorder comprising deficits in behavioral inhibition, sustained attention and resistance to distraction, and the regulation of one’s activity level to the demands of a situation (hyperactivity or restlessness).

There are three types of ADHD:

Some scholars view ADHD as a disorder of self-regulation or executive functions rather than an order of disruption.

Here are ways to support students with ADHD:

References

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Fact Sheet. LD Online. Retrieved from http://www.ldonline.org/article/Attention_Deficit/Hyperactivity_Disorder_Fact_Sheet

Brown, T. E. (2005). Attention deficit disorder: The unfocused mind in children and adults. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) is an auditory deficit that makes distinguishing sounds challenging. It is not the result of higher-order cognitive, language, or related disorders (ASHA.org).

Students who have been diagnosed with APD, sometimes called Central Auditory Processing Disorder (CAPD) may struggle with one or more of the following:

Here are ways to support students with APD:

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2005). (Central) auditory processing disorders.

Understood for All, Inc. (2020). Auditory Processing Disorder: What You Need to Know. https://www.understood.org/en/learning-thinking-differences/child-learning-disabilities/auditory-processing-disorder/understanding-auditory-processing-disorder

Students with dyscalculia often struggle with math calculation skills and find difficulty in number representation, number processing, quantifying sets without counting, using nonverbal processes to complete simple numerical operations, and estimating relative magnitudes of sets. Quantitative reasoning may also be impaired for individuals with dyscalculia.

Here are ways to support students with Dyscalculia:

References

Berninger, V. W., Wolf, B. J., & Berninger, V. W. (2016). Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, OWL LD, and Dyscalculia: Lessons from Science and Teaching. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Child Mind Institute (2019).How to Spot Dyscalculia. https://childmind.org/article/how-to-spot-dyscalculia/

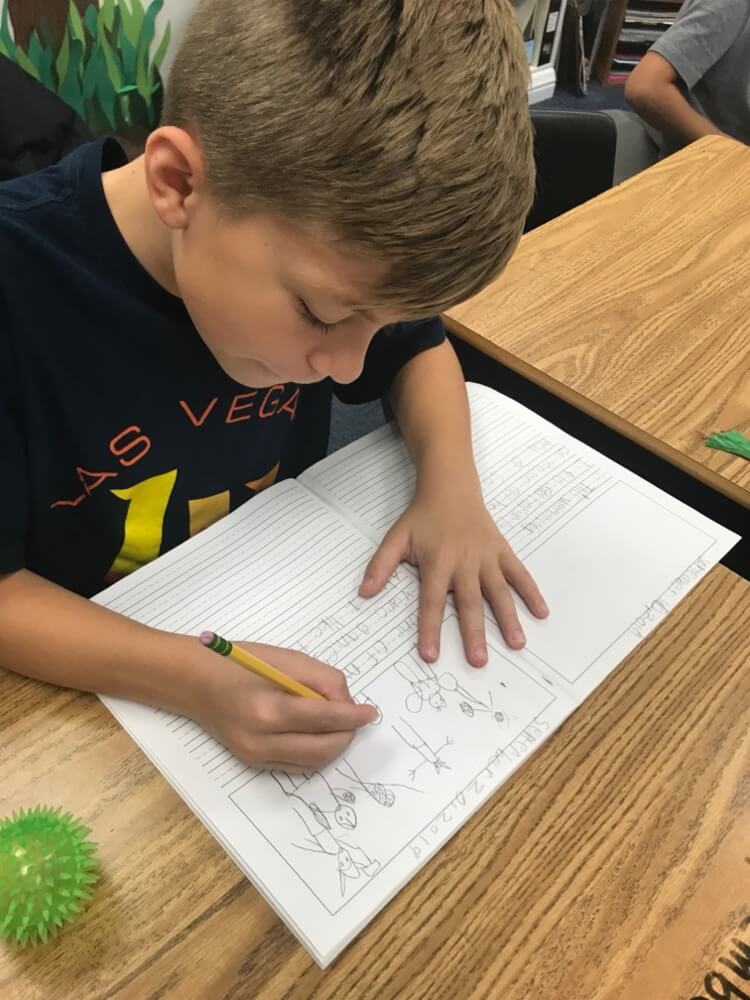

Dysgraphia impacts a student’s handwriting and fine motor skills. Impaired ability to reproduce legible and automatic letter and numeral writing. Students with dysgraphia may also struggle with planning and organization.

Here are ways to support students with dysgraphia:

References

Franklin, D. (2018). Helping Your Child with Language-Based Learning Disabilities (Strategies to Succeed in School and Life with Dyscalculia, Dyslexia, ADHD, and Auditory Processing Disorder) (1st ed.). New Harbinger Publications.

International Dyslexia Association (2015). Understanding Dysgraphia Fact Sheet. https://dyslexiaida.org/understanding-dysgraphia/

The International Dyslexia Association defines dyslexia as, “a specific learning disability that is neurological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include reading problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede the growth of vocabulary and background knowledge” (Mather & Wendling, 2012, p. 11).

Here are ways to support students with dyslexia:

References

Mather, N., & Wendling, B. J. (2012). Essentials of dyslexia assessment and intervention. Hoboken, NJ: J. Wiley.

Shaywitz, S. E., & Shaywitz, J. (2020). Overcoming dyslexia. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Executive functioning skills are “brain-based skills required for humans to effectively execute, or perform tasks and solve problems” (Guare, Dawson, & Guare, 2013, p.11). Executive functioning includes working memory, planning, prioritization, organization, time management, activation, self-control and self-awareness, task initiation, flexibility, sustained attention, and time management. Executive dysfunction is a relatively new term used to describe individuals who may find challenges executing these skills.

Here are ways to support students who struggle with executive functioning:

References

Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2018). Executive skills in children and adolescents: A practical guide to assessment and intervention. New York: Guilford Press.

Cartwright, K. B. (2015). Executive skills and reading comprehension: A guide for educators. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Receptive language disorders occur when individuals have trouble understanding words they read. Expressive language disorders are characterized by having trouble speaking with others and expressing thoughts and feelings. Language disorder is not hearing impairment. Students with language disorder, which may be referred to as receptive-expressive disorder, have difficulty expressing themselves and understanding what others are saying, however, they are able to produce sounds and their speech can be understood by others.

Here are ways to support students with language disorder:

References

Kaderavek, J. N. (2015). Language disorders in children: Fundamental concepts of assessment and intervention. Boston: Pearson.

Understood for All Inc. (2020). Language disorders: What you need to know. https://www.understood.org/en/learning-thinking-differences/child-learning-disabilities/communication-disorders/what-are-language-disorders

People-first language conveys respect for the individual by emphasizing the fact that they are more than their disability. First and foremost they are people.

People-first language examples include: (a) students with learning disabilities (rather than learning disabled students) and (b) students with exceptionalities (rather than special needs students).

Instead of defining people primarily by their disability, people-first language conveys respect by emphasizing the fact that people with disabilities are first and foremost just that—people.

Reference

Snow, K. (2007). People first language. Disability is natural.

As students with language based learning disabilities move through their school years, it is especially important to develop self-advocacy skills and guide students as they deepen their self-concept. Self-advocacy empowers students to speak up for themselves and make decisions important for their lives. Self-concept, as defined by the American Psychological Association, is “one’s description and evaluation of oneself, including psychological and physical characteristics, qualities, skills, roles, and so forth” (APA.org).

References

Garner, P., & Sandow, S. (Eds.). (2018). Advocacy, self-advocacy and special needs (Vol. 25). Routledge.

James, Nancy (n.d.) Self Advocacy: Know Yourself, Know What You Need, Know How to Get It https://www.wrightslaw.com/info/sec504.selfadvo.nancy.james.htm

A neurological condition, sensory processing disorder, may make the acquisition of knowledge and skills received through the sense more difficult. Receiving messages from the senses and turning them into developmentally appropriate motor and behavioral responses are characteristics of sensory processing disorder (additudemag.org). Sensory processing disorder is not listed as a condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) and is not considered under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) a specific learning disability.

Here are ways to support students who experience sensory processing disorder:

References

Miller, L. J., Fuller, D. A., & Roetenberg, J. (2014). Sensational kids: Hope and help for children with sensory processing disorder (SPD). NY, NY: Penguin Group.

Arky, B. (2020). Sensory Processing Issues Explained. https://childmind.org/article/sensory-processing-issues-explained/

Specific Learning Disability means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell or do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia. Specific learning disability does not include learning problems that are primarily the result of: visual, hearing, or motor disabilities; intellectual disability; serious emotional disability; cultural factors; environmental or economic disadvantage; or limited English proficiency (U.S. Department of Education, IDEA Sec. 300.8 (c) (10)).

Here are ways to support students with specific learning disabilities:

References

Flink, D. (2014). Thinking differently: An inspiring guide for parents of children with learning disabilities. New York, NY: William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins.

Reid, R. C., Lienemann, T. O., & Hagaman, J. L. (2013). Strategy instruction for students with learning disabilities. New York: The Guilford Press.

Social communication disorder may make it difficult to talk with people in socially appropriate ways. Students who have been diagnosed with social communication disorder struggle with the pragmatics of spoken language, the unspoken, subtle rules of speech that allow people to connect with one another.

Here are ways to support students with social communication disorder:

References

Mandy, W., Wang, A., Lee, I., & Skuse, D. (2017). Evaluating social (pragmatic) communication disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(10), 1166-1175. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12785

Smith, S. (2020). Parenting Children with Learning Disabilities, ADHD, and Related Disorders. https://ldaamerica.org/info/what-do-parents-of-children-with-learning-disabilities-adhd-and-related-disorders-deal-with/

The National Center for Learning Disabilities (NCLD) defines visual processing disorder as a hindered ability to make sense of information taken in through the eyes. This is different from problems involving sight or sharpness of vision. Difficulties with visual processing affect how visual information is interpreted, or processed by the brain.

Here are ways to support students with visual processing disorder:

References

LD Online (n.d.). Visual and Auditory Processing Disorders. http://www.ldonline.org/article/6390#anchor520397

Understood for All Inc. (n.d.). Visual Processing Issues. https://www.understood.org/pages/en/learning-thinking-differences/child-learning-disabilities/visual-processing-issues/

Apraxia of Speech is a motor speech disorder that makes it hard to speak (ASHA.org). Working with a speech-language pathologist learning how to say sounds and words better supports students with Apraxia. The broader umbrella of dyspraxia is characterized by difficulties coordinating one’s physical actions. Apraxia of speech/dyspraxia does not impact intelligence; most people with apraxia of speech/dyspraxia have average to above average intelligence.

Here are ways to support students with Apraxia:

References

American Speech Language Hearing Association (n.d.). Childhood Apraxia of Speech. https://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/childhood-apraxia-of-speech/

Lindsay, L. (2020). Speaking of Apraxia: A parents' guide to childhood apraxia of speech. S.l.: Woodbine House Inc., U S.

Visual memory weakness – the word is not sticking. A traditional learner would need to see the word at least 12 times for it to be a part of their automatic response. The struggling reader needs to be exposed to the word as many times as possible. There needs to be automaticity and fluency in order for the word to become a part of the child’s lexicon.

Most spelling lists are based on rote visual memory. With enough practice the student can hold on to the image similar to a crash course of study but that image is only held in memory for the short term. A child cannot spell better than he reads; reading and spelling should be linked. The more meaningful and connected you can make the image, the greater chance of retention.

Students are wedded so much to the print and decoding the word that no more energy is left to make the picture. These students need strategies not only to improve word attack but reading fluency. Until they develop a reading rhythm or prosody they will be unable to make “the picture.”

Students with weak receptive and / or expressive language skills have very vague pictures and need to be taught how to make a more vivid movie – how to “visualize”.

Fractured programs that are not integrated through the curriculum or school day. The intensity of the program is not there

“We use a little bit of this and a little bit of that”.

“It’s Orton-like”.

“He has Wilson Reading 1/2 hour a day” are common scenarios.

The programs were not designed to match the learner. Testing should drive the IEP which should drive the PROGRAM. Instead, the child gets what the school has as far as the program no matter what the need is.

Very important to remember that no one ever grows out of a learning disability but if given the appropriate tools, will be successful, giving the appearance of “growing out” of it. The tools necessary require direct instructions. It cannot be assumed that the child will pick them up incidentally; otherwise he would have already.

A child who shows significant language delays or difficulties may be considered at risk. Children who have had early onset learning issues, i.e. chronic ear infections, may be at risk. Children who struggle with rhyming, are slow to learn the connection between letters and sounds, unable to recall the right word, slow to add new vocabulary words, unable to follow multi-step directions are at risk. In order to have reading success, these prerequisites must be in place. If children who are struggling with reading get effective phonological training in kindergarten and first grade, they will have significantly fewer problems learning to read at grade levels than do children who are not identified or helped until third grade.

For more information on ways of giving or to make a donation online you can clicking here.

Lower/Middle School

15 Tower Hill Rd

Mountain Lakes, NJ 07046

Phone 973-334-1234

Fax 973.334.2861

Craig High School

24 Changebridge Road

Montville, NJ 07045

Phone 973.334.1234

Fax 973.334.1288

Administration

10 Tower Hill Road

Mountain Lakes, NJ 07046

Phone 973-334-1234

Fax 973 334 1299