Introduction & Rationale

Background

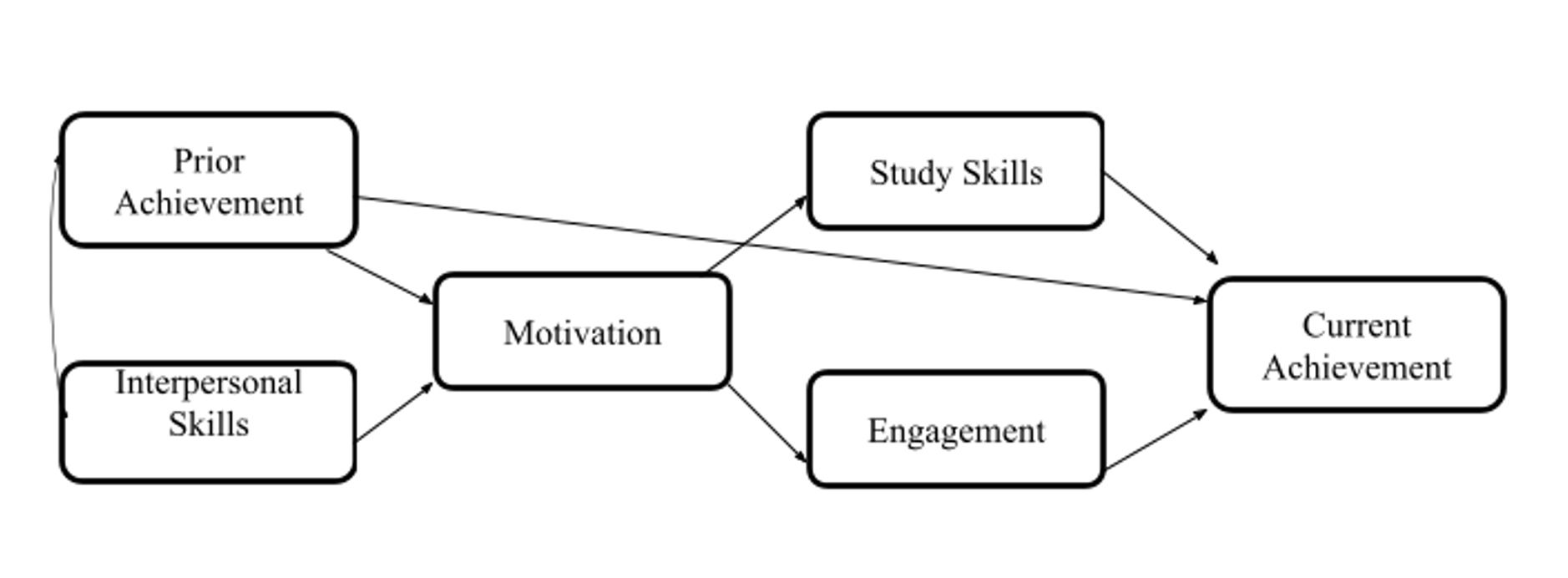

Teens with ADHD experience greater levels of academic impairment than students without ADHD. Academic enablers, non-cognitive skills and behaviors, like study skills, engagement, motivation, and interpersonal skills are essential components to optimal academic attainment. For students with ADHD, these skills tend to be underdeveloped. This study explored the attitudes, thoughts, and perspectives of students in high school diagnosed with ADHD in regards to their challenges, their strengths, and their experiences as students. As children gain more autonomy, listening to their voice is an important step on their path to self-advocacy. To inform the understanding and development of models for effective intervention that are accepted and readily adopted by teenagers with ADHD, interviews conducted with 16 students examined academic enablers from their perspective. Results from these interviews create an authentic context for exploring student perspectives about (a) the social self, the student learner in relation to teachers and peers, and (b) the individual self, and (c) the student’s use of self-regulation, self-management, and self-expression as they become more autonomous individuals with increased responsibilities for their own learning. This study examines high school students’ experiences and perspectives of their ability to learn and experiences in the classroom, the interventions teachers have taken with them, exposure to stigmatization, engagement in student agency, diagnostic labeling effects, and their self-concept (Owens & Jackson, 2017; Wiener & Daniels, 2016).

Need for Study

Persisting into adolescence and adulthood, educational impairment impacts 50 to 80% of youth with ADHD (DuPaul, Stoner, & Reid, 2014). Critical skills for students in secondary schools include the ability to engage executive functions and self-regulatory behaviors, such as planning and organization, all predictive of future academic attainment (Barkley, 1997; Volpe et al., 2006).

A large body of research exists exploring the role of behavior in academic attainment for elementary students as well as students in college. However, the cannon of literature exploring the experiences of teenagers with ADHD in relation to their acquisition of academic enablers leading to educational attainment as they navigate more autonomy, less parent, teacher, and school supports and structures, and increased independence are scant (Bolic Baric, Hellberg, Kjellberg & Hemmingsson, 2016; DiPerna, 2006; Kent et al., 2011; Wiener & Daniels, 2016; Wu & Gau, 2013).

Research shows that teenagers may be resistant to academic supports they view as stigmatizing or labeling (Bussing et al., 2016; Owens & Jackson, 2017). To inform understanding and development of models for effective intervention that are accepted and readily adopted by teenagers with ADHD, a closer look at academic enablers from their position is essential (Wei, Yu & Shaver, 2014).

Research Questions

Methods

Interview Questions

Emergent Themes

Individualized/Modulated Pacing

“So like, I also like individualized learning. So like, here, it's amazing because like, there's smaller class size and then there's also study hall that you can go to. And I really like that because then you get more time with the teacher individually. So I like it, I like when I know that I can have help individually.”

-JA, 12th grade

Teacher Directed Learning and Attention

“I'm a very, I learned by talking through things and or doing them. If a teacher is willing to talk with me about the subject, not not particularly be very restrictive on it. My brain has a very odd way of making connections. So a lot of the times if a teacher is willing to go with me on one of my weird metaphors I'll understand the subject...it just...it helps me to talk it out and say, Okay, well, it's like this and this, right? And if they say yes, then that's great. If it's no, then it's another try. And I've always found that the best way for me to learn.”

-OL, 12th grade

“And so we wrote it all down, and then we put how much time I think it's going to take, so that helped with my organization, because then that actually, it actually worked because I spent a certain amount of time on each thing and I got it done. So, she's, she's amazing with that. She's really great at organization.”

-SB, 11th grade

Passive Peer Mentoring

“Yeah, because I know that other people are you know, more focused and can do things faster. So if I have …it's sort of like cross country running, if I have someone who can pace myself. Then I can, I work a lot better.”

-FP, 10th grade

“...not doing it in my room. I just can’t concentrate. I need someone kind of there, to, like help me. Like, it’s weird. If someone’s like sitting next to me while I’m doing work, I’m doing it much better than when I am by myself.”

-KS, 10th grade

Self-Concept: Identity

“When I was a lot younger, my mom went to multiple doctors and asked them if I was autistic. And, you know, so on and so forth. There were quite a few different diagnoses that came up over the years. So, needless to say, the ADHD wasn't really a new thing for me to be diagnosed as…And parenting is hard. And when you can't find an answer for why your child is behaving like this, or why your child isn't behaving like this. It can be scary, which I understand. And I also have to know that that wasn't the correct behavior that, you know, they should have been a little more considerate.”

-OL, 12th grade

Self-Concept: Belonging

“I felt like I was different from everyone else…That was when I was first diagnosed. But then, like, as I learned more about ADHD, I’m like, no, I’m no different. I just have this thing….that kind of makes it harder for me to learn and focus.”

-JA, 12th grade

Self-Management

“Because in order to keep myself physically organized, I have to keep myself mentally organized. So like to have like to have it all organized. I try to stay on top of it, if not ahead of what's going on. Not only because I really don't like doing homework outside of the school hours, but also because when I do homework outside of school hours, it's kind of like, I get more distracted and more like, oh, I don't want to do this.”

-SS, 11th grade

Self-Awareness

“I been very good about adapting and knowing exactly what I need when I need it. Because otherwise, I’m just not going to succeed.”

-OL, 12th grade

Attention/Focus

“I'll be talking and all of a sudden, my mind just goes faster than I'm talking. I'm just like…I start fumbling on words. I'm like, I have to chill for a second. I can't talk right now. Because my mind is already like, 10 words of head of what I was already saying…”

-KS, 12h grade

Self-Expression

“I like to do whatever I can get my hands on, basically. I will do anything I can. Like, I can do fashion design. I can sing songs. And I’m learning to write songs. I’m just great at painting. I’m great at a lot of things.”

-KQ, 9th grade

Conclusions

Results from the study revealed the challenges that teenagers with ADHD face along with their perspectives on identity, self-expression, and sense of belongingness. Balancing teacher-led scaffolding and collaborative learning opportunities with peers may be one means to address the interplay of dependence moving to independence as a learner. As students mature, their responsibilities are expected to increase. However, these 16 participant interviews and observations indicate there are varying levels of student readiness to move in the direction of self-agency and autonomy. Many teens continue to need support with basic study skills like organization, prioritization, planning, and time management. Additionally, engaging the student in work that is meaningful to them gives them a greater sense of ownership over the process of learning, and increases their ability to attend to the task. Teachers who give students choice in the type of task (e.g. essay instead of multiple choice test, or project rather than worksheet) are able to leverage the students’ buy-in and innate motivation to get the work done. Teachers are encouraged to allow the students to use multiple means to represent their learning, encouraging the student to tap into their affinity for self-expression. Finally, increasing relevant pre-service training for teachers would not only benefit students with ADHD, but all learners so that teachers are equipped with a toolbox of instructional strategies and interventions that far exceed the traditional needs in the high school classroom.

For more information on ways of giving or to make a donation online you can clicking here.